Finding the common ground with executives in incidents

I spotted this thread on Reddit, discussing the pains of executives dropping into incidents, and the corresponding impact it can have on the incident response process.

Being an SRE community, it was a little more of a one-sided account of the situation. So let’s look a little closer, and dive into what it takes to make incidents more efficient for responders and executives alike.

You’ve been paged, the dashboards are a sea of red, and given the alerts that are firing, you suspect the database is the problem. You dive into your terminal and start issuing a stream of commands to see what’s up.

The more you pull on the thread, the deeper you go into your debugging hole, and the more you’re consumed with finding the problem.

And then you notice your Slack notifications. You’ve got unread mentions, and see your CTO has been @‘ing you for the last 10 minutes.

Now your focus is split across managing the incident, and managing the angry and impatient executive.

If you’ve found yourself dealing with this situation in the past, you’ll know it’s not fun. But it can be better.

When you understand the situation from both sides, you’ll see there’s a few easy ways to find common ground on which incident responders and executives can work together to resolve incidents efficiently.

Responders need space to focus on effective mitigation

In the middle of an incident, the responder’s default focus is normally on addressing the problem at hand. It makes perfect sense; the issue you're dealing with is causing some negative impact, and mitigating that impact as fast as possible is entirely logical.

But in many cases, this singular focus is short-sighted. And in the context of executives dropping into incidents, if you're off in your terminal firing of CLI commands, or diving into your dashboards to dig into numbers, you’re leaving behind a communications vacuum.

With no comms, people get nervous. And among those people is the executive who comes looking for answers.

Executives just want to know everything is OK

“In my experience, roughly half the time an exec is causing problems in an incident, it's because they're unaware that they're disrupting things or else they'd step out. The other half is because they know something big is happening that affects their job but they aren't getting the information they need.”—reddit user

Whilst it’s easy to point fingers at executives negatively impacting incident response, it’s important to empathize with them in this situation.

All signs point to organizations trying to hone in on exactly how much downtime is costing them, and a myriad of other pressures all weigh on their minds, too.

Executives are responsible to boards of directors, investors, shareholders, customers and ultimately their employees.

So while it may seem like executives are just being difficult, when you take a deeper look, their reasons for jumping in often makes sense.

- Executives want to know that the right things are happening during an incident and the appropriate people are on it. In the absence of this clarity, lots of assumptions can get made. “Who’s dealing with this right now? Is it a junior engineer or someone more tenured?” Without a clear answer to these questions, anxiety grows

- They are the ones that ultimately need to make decisions when things go very wrong, so comms are critical for them. If they aren’t equipped with the right answers during a particularly bad incident, it can make the company look even worse

So when a high-severity incident gets declared, it’s easy to understand how the focus quickly turns to “I need to know what’s going on here because I want a sense of how much it’s going to cost us,” or something to that effect.

Executives are responsible to boards of directors, investors, shareholders, customers and ultimately their employees. The more downtime is experienced, the more it jeopardizes a litany of things. So it’s fair for them to have questions and wonder what the state of things are and whether or not everything is going to be OK.

Actionable ideas for improving responder and executive interactions in incidents

Responders just want to focus on dealing with incidents. Executives just want to know that the response process is playing out smoothly, and stay in the loop as much as possible.

Thankfully, there are a few ways to keep everyone on the same page.

When you’re responding, leave a trail of what you’re doing

In the absence of information, people will assume the worst.

Oversharing is your friend here. Any action you take, regardless of how insignificant it may seem, is probably worth communicating.

“The CEO should be told about the incident via a public channel. In that announcement you should state: What specially is happening and who it impacts, what the expected resolution time is and when the next update will come. The reason why people start stressing out is because they don’t know what to expect, how to find information and/or when new information has become available.”—reddit user

This visceral sense of activity immediately diffuses nerves and can help executives feel a bit more at ease knowing that there’s constant movement towards a resolution.

Agree on triggers for executive comms

The word “proactive” is going to come up a lot here. The best way to get ahead of questions is by answering them ahead of time. With incidents, certain types will be of more interest (and impact) than others.

So set up agreed-upon triggers that let you know it’s time to communicate with executives. For example:

- Incidents over a certain severity

- Incidents that affect certain customers

- Incidents that have a certain monetary impact

More often than not, these are exactly the types of incidents that will generate the most anxiety, so communicating once any of these alarms have gone off is a good first step towards letting folks know you have things under control.

Introduce an internal communications role for higher severity incidents

Having a dedicated person and/or channel responsible for executive comms can go a long way here. Why? Because when incident responders are fighting fires, it’s helpful for them to not also have to concern themselves with sharing updates. And updates are just the start, the barrage of questions that follow can make this a full-time position!

Your incident response processes should leave as little room for ambiguity as possible. Document the process in a place everyone, not just the executive team, can find.

It’s important that the person responsible for communicating can do so in a way that’s appropriate, hitting the right details without overwhelming the recipients. While executives with technical backgrounds are much more common these days, when something bad is happening, the last thing they want to be doing is parsing through highly complex explanations of databases losing quorum.

Think of this as an executive summary: concise, to-the-point, need-to-know information.

“Depending on the scale and length of the incident, you'll have multiple channels, each with a leader responsible for inter-channel communications. Everyone should know who their channel leader is…”—reddit user

By having a dedicated channel for them, with updates contextualized around business impact and an expectation around the frequency, it’s considerably easier for executives to stay in the loop, and the pressure on responders relieved as a result.

Should they have any questions that aren’t being answered by your updates, having one person dedicated to responding to them can also help. But it’s important to make this clear at the onset. There should be no ambiguity about who this person is.

“If you have any questions that aren’t answered by our incident updates, please tag Sally and she’ll get back to you ~10 minutes.”

Ultimately this person should serve as the gatekeeper here and facilitate smooth comms.

Have a mutually agreed upon incident response process to leave zero doubt

Help your executives help you!

Your incident response processes should leave as little room for ambiguity as possible. Document the process in a place everyone, not just the executive team, can find.

Alerting, declaration, roles, escalations, internal and external comms. Everything.

What’s your process for communicating? Where should folks go if they don’t have the answer to something? By proactively answering these questions, you’ll avoid situations where people feel like they need to go chasing answers.

“Look into playbooks and create a standard procedure for handling incidents. Triaging, who to contact, what to do, etc. Add to these playbooks over time. Ensure your CEO is told about incidents (of specific severities) after they’re handled to help build trust in the process.”—reddit user

By not being proactive about communication here, you leave a lot of room for assumptions and this is when nerves go on high alert.

Don't leave your process to chance

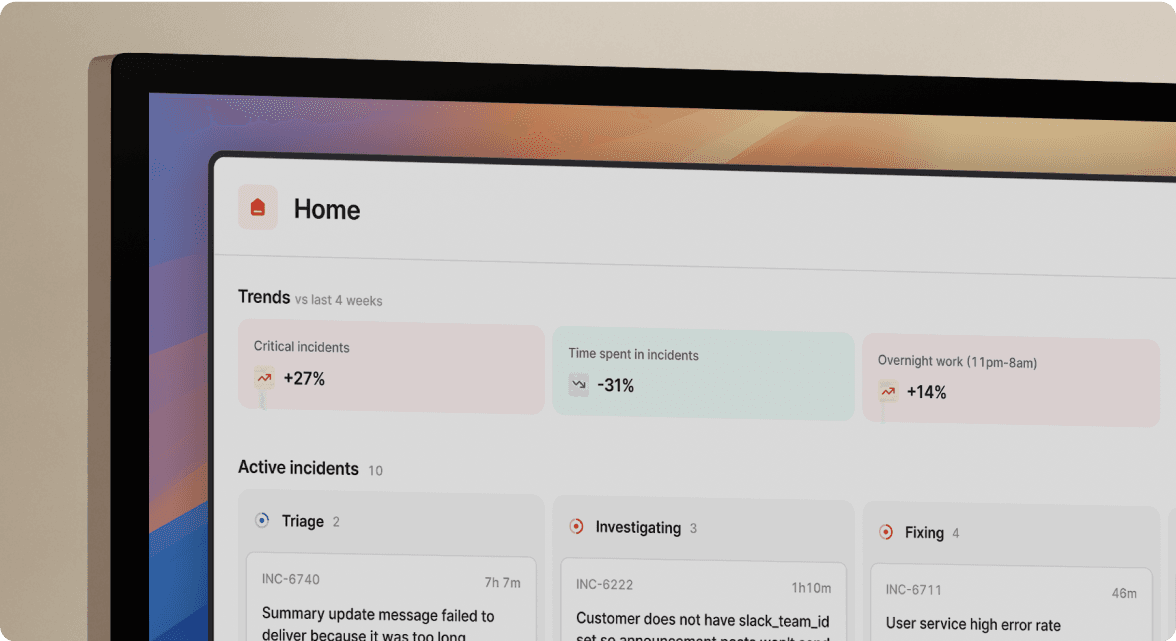

Whilst documenting your response goes a long way, getting your processes into a place where documents aren’t required is even better. The best way for folks to know what to do in an incident, is to provide them instructions when it’s contextually relevant. This is exactly where incident.io can help!

Use your post-incident process to seek and act on feedback from people at all levels, not just engineers

All of these processes are living things. There’s always room for improvement and things you can do to make everyone feel more confident in the process.

It’s tempting for post-incident learning to be focused on the actual issue you face, with the incident process itself falling down the priority list. But digging into the details on how you responded is equally important, and the post-incident process is perfect for gathering input from folks at all levels, particularly executives.

Remember, executives ultimately want to know that everything is running efficiently, but you also need the space to manage the incident. To marry the two together, you can consider asking some of the following questions during a post-mortem meeting:

- Did you see anything during our response process that concerned you?

- How often do you expect comms during an incident of similar severity?

- Is there any context that we didn’t provide that would’ve been helpful for you to have?

- During an incident of X severity, what do you need to know immediately to be able to have more confidence in our response?

By getting answers to these questions directly, you’ll be able to make any necessary changes to your response process so that you can focus on the incident, and executives can be primed with the knowledge they need at the onset.

Incident management is a team sport

Incident management is not solely about response. It’s about your entire organization coming together to resolve incidents as quickly as possible. But if there’s a sense of “us vs them” or, in this case, “engineers vs executives,” it can be hard to leverage the expertise of everyone involved.

This can quickly turn into a much bigger problem down the line. When folks feel like their well-meaning opinions aren’t being heard or their questions aren’t being answered proactively, this is when they’ll feel like they have no choice but to chase them.

Executive teams ultimately want to know that things are being handled by the folks best equipped to do so. Incident management is no exception.

No one wants to field a list of questions during the middle of an incident—but to avoid this you have to be proactive about a few things:

- Answering any questions before they come up. Process documentation is your effective ticket here

- Overshare during incidents! Big gaps between updates leaves a lot of room for assumptions and, eventually, questions

- When questions do come up, filtering them into the appropriate channel to be handled by a single designated person

- Loop executives into any iterations of your response process so they feel heard and their expertise and perspective is integrated

As long as you’re covering these bases, you should be in a better position to focus on the incident while giving executives the context they need to be helpful, and ultimately help the organization.

Remember, everyone feels the pain of incidents. But as long as everyone is on the same page, you can run them more effectively and mitigate any fallout before it happens.

I'm one of the co-founders, and the Chief Product Officer here at incident.io.

See related articles

How communication can make or break your incidents

In this episode, Pete and Lisa discuss why great communication (both internally and externally) is essential to the success of any incident management process.

Charlie Kingston

Charlie Kingston

Our A, B, Cs of external communications

External communication is really important. But you have to make sure you’re hitting a few key bars before you ship things out into the world.

Lisa Karlin Curtis

Lisa Karlin Curtis

How to communicate on your status page

Great communication with your customers can quickly turn a negative into a positive. We lay out our five steps to better incident communication.

Chris Evans

Chris EvansSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization