Why you should ditch your overly detailed incident response plan

When critical incidents happen — which they inevitably do 😅 — and you’re in the middle of trying to figure out what the best thing to do is, it can feel comforting to know that you’ve got a pre-prepared list of instructions to follow, commonly known as an “incident response plan”:

An incident response plan is a document that outlines an organization's procedures, steps, and responsibilities of its incident response program

In theory this sounds quite simple, and a typical flow you might envision is:

- An incident is declared

- I’ll triage what might have happened

- I’ll refer to my incident response plan and follow the detailed instructions step-by-step

- Incident is resolved 🎉

It might be tempting to think that the hardest part of running incidents is finding or writing a checklist that exhausts all of the things that could go wrong. Once written you’ll repeatedly refer to it in future incidents, following the detailed instructions whilst you’re trying to do everything else that’s required during an incident.

A quick Google search further validates this view. We spent some time looking for incident response plans online and found a wealth of detailed lists (focused on cyber security/data breaches) titled:

- What are the 7 steps to follow in incident response?

- What are the 5 stages of an incident management process?

- What are the 6 basic steps of an incident response plan?

This is usually coupled with a variety of multi-page (some as long as 30 pages 😅) PDF templates, that all guarantee that theirs is “comprehensive” and that following it will “ensure you’re prepared”. These cover a variety of topics, including:

- Planning scenarios

- Notification, escalation and declaration procedures

- Sequence of events to follow when incidents happen

These long documents will usually have numerous placeholders where you can “insert your business name here”, so you can feel like you’ve personalised it to your company’s needs.

Whilst the detail and length of these documents might provide some readers with a feeling of rigour, there’s a few reasons why we believe this approach is flawed:

- Every org and product is different: If you think about all of the nuances that your company and product has, it’s unlikely that going through a detailed template is going to be very useful for your needs.

- Incidents shouldn’t be contained to one area of the business: Most of the resources we found were constrained to cybersecurity teams. We wrote a detailed chapter in our Incident Management Guide called “defining an incident” which outlines how we think about incidents; one of the key takeaways is that it’s highly valuable to normalise declaring incidents across different teams in your company.

- The practicalities of running an incident: Let’s face it, when you have an incident on your hands there are a lot of things to think about. Do you really want to add a long template that you need to go back and forth from, to the list of things you already need to be thinking about (triaging the issue, internal/external comms, identifying a fix, etc.)

To put it simply (and borrowing from a commonly used Mike Tyson quote): “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the face”. It’s because of this we believe that overly detailed plans and long “comprehensive” documents are not as useful as they might initially seem.

So what should you do instead? - here’s some practical things we recommend:

- Encode and automate your processes

- Normalise declaring incidents (especially outside of engineering)

- Practice, practice practice

Encode and automate your processes

All incidents are unique, and by definition a break from expected or ‘normal’ work. You’ll often find yourself dealing with unfamiliar situations and needing to improvise under pressure.

But, underneath the complexity and unfamiliarity of every incident, is a process. The same process. A repeatable process. We recommend outlining the common steps between incidents which we’ve written in our Incident Management Guide chapter on response.

We don’t believe these steps should be written and documented away, in the hope that others will find (and refer to) it when an incident is declared. Whatever tools you use to deal with incidents, these steps should be encoded into them so they help (rather than hinder) you during an incident.

Your mental bandwidth should be occupied with the incident at hand rather than trying to remember whether you remembered step five of your incident response plan. Next time you’re dealing with an incident, your tool should prompt and (ideally) run the step for you.

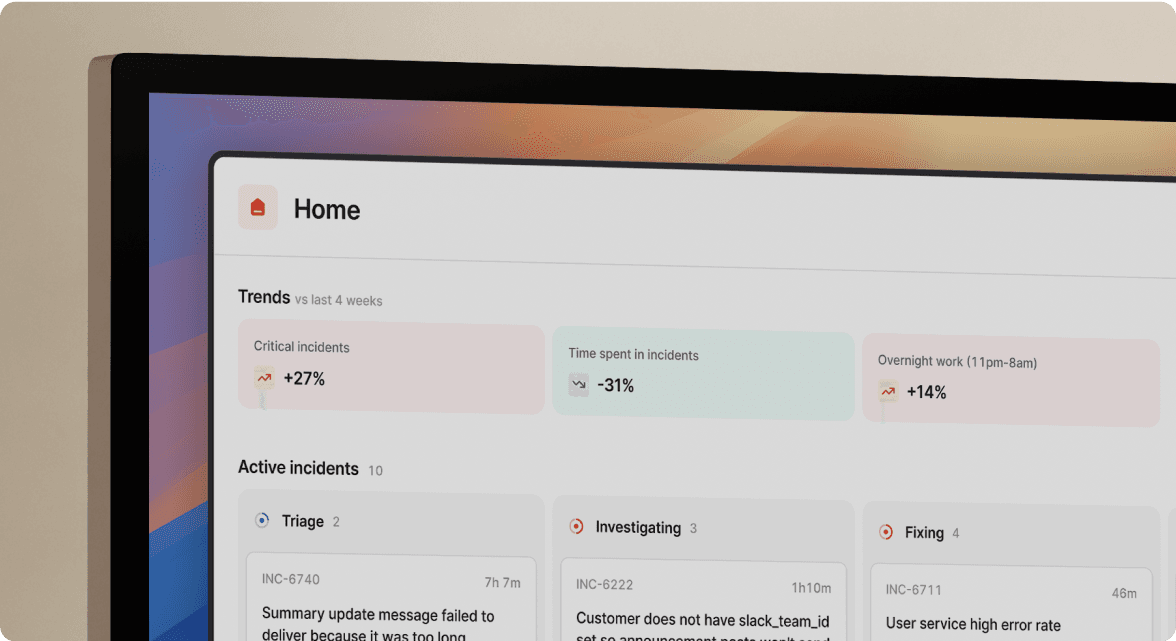

💡 If you use incident.io: use a combination of custom fields to encode the logic that matters to your company, and workflows to automate your incident response process

Normalise declaring incidents (especially outside of engineering)

Organizations generally set their threshold for incidents high, where only the most severe events are called incidents. We believe smaller incidents are extremely valuable, and there's a lot of upside from lowering your threshold for an incident.

Smaller incidents are a great way to learn about the failure cases of systems and provide an opportunity for teams to practice how they’d respond to larger issues.

ℹ️ Our definition of an incident is anything that takes you away from planned work with a degree of urgency.

Additionally, many organizations view incidents as a solely engineering concern. Our experience is the polar opposite. Incidents often start in product/engineering, but they usually require people from around the organization to form a temporary team to collaborate, communicate and solve a problem.

Imagine a significant outage at a payments fintech like Stripe. The source of of the issue might have started in engineering, but it’s not long before others need to get involved. Customer support and public relations need to start communicating publicly as soon as possible. Engineers begin discussing potential resolutions, including a rollback. Legal need to get involved to understand any potential contractual implications. Compliance need to get involved to ensure that they’re following the regulator’s guidance. An executive is pulled in to make the final call. Responding is a whole-organization effort.

Ensuring non-engineering teams are familiar with the process of running an incident means you’re well placed next time you have a time critical incident that requires input from non-technical teams; this also has an added benefit of allowing those teams to declare incidents themselves - potentially saving you critical time in future incidents.

💡 If you use incident.io: type /inc or /incident from any channel in Slack to pop up the incident creation form; alternatively click the 3 dots on a Slack message to “create an incident”

Practice, practice practice

Finally, one of the many reasons we don’t believe having overly detailed documentation is useful - is that it can provide you with a false sense of security. Writing a perfectly structured, neat document makes no difference to you, your team or your company when a critical incident happens. In fact, the more effort you’ve put into structuring your process, the more fractured you risk becoming if your teams aren’t trained to follow that process.

Thankfully, it’s easy to fix this by setting aside dedicated time for your teams to practice. Read our "practice or it doesn’t count" chapter in our practical guide to incident management for a detailed breakdown of how we’d recommend you to practice incidents with your team.

To conclude, if you want to ensure you’re well prepared for your next critical incident; make sure you have more than a neatly written document/list of steps written. Build this logic into your incident management tools, lower the severity of what you classify as an incident and practice with your team as much as possible.

See related articles

Secure access at the speed of incident response

Blog about combining incident.io's incident context with Apono's dynamic provisioning, the new integration ensures secure, just-in-time access for on-call engineers, thereby speeding up incident response and enhancing security.

Brian Hanson

Brian Hanson

Everything you need to know about ITIL 5, AI and incident management

We break down ITIL 5's governance framework and what it means for teams using AI in incident response. For incident management, it addresses questions like: Who's accountable when an AI-suggested remediation backfires? How do you audit AI-generated updates?

Chris Evans

Chris Evans

DevEx matters for coding agents, too

When AI can scaffold out entire features in seconds and you have multiple agents all working in parallel on different tasks, a ninety-second feedback loop kills your flow state completely. We've recently invested in dramatically speeding up our developer feedback cycles, cutting some by 95% to address this. In this post we’ll share what that journey looked like, why we did it and what it taught us about building for the AI era.

Rory Bain

Rory BainSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization