No capes: the perils of being a hero-engineer

When I first started out as an engineer I really leant in to the idea of what’s often called “being a hero”; I would get to the office a bit early to make sure I could fix anything that had gone wrong overnight. I loved the camaraderie of someone outside engineering bringing their laptop over with a critical process broken for me to fix (even if I’d been the one to break it!).

Being a hero feels really good for a while, but over time, it loses its shine.

People start expecting you to take on every emergency, so you don’t get praised for it any more. The company grows and the number of fires you’re fighting increases. You probably have important company goals you’re expected to be contributing to.

It’s easy to start to start feeling stressed out, under-appreciated and struggle to find the time to work on anything else.

I’ve been on the other side of this as well. Incidents are an incredibly effective way to learn, so when you show up to a new job where there’s a hero (or group of heroes) jumping in to fix things constantly, it’s frustratingly slow to understand how everything fits together from the outside. There’s hints dropped in Slack and breadcrumbs in pull requests but all the discussion has happened in a private chat elsewhere.

It doesn’t have to be this way. Here’s the advice I wish I’d listened to earlier.

Be open, and let people in

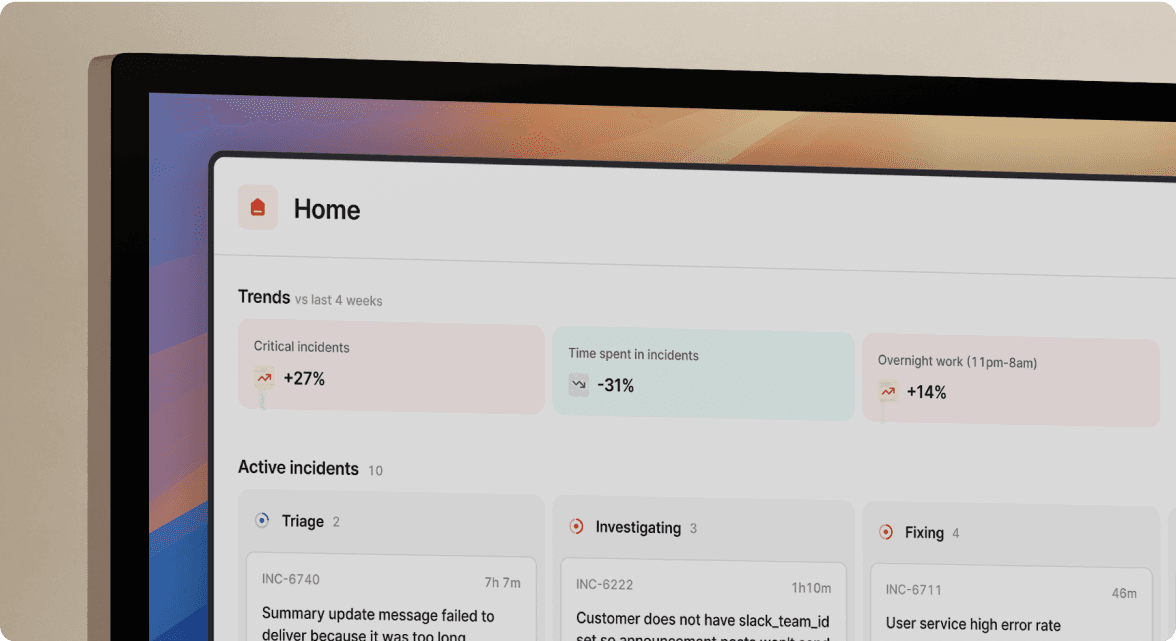

Whether you can feel yourself becoming a hero, or it’s someone you manage, the key to breaking the vicious cycle is to bring more people in to incident response. You can only do this with open and transparent communication. If everyone in the team can see what incidents are happening, and easily catch up on the situation, they’re probably really keen to come help out.

This won’t fix everything overnight. You might be talking to yourself in a channel for a while, but you’ve opened the door.

Pick a role and do it well

Part of what makes being a hero stressful is doing everything. As Ron Swanson said, “never half-ass two things, whole-ass one thing”.

Incident response is hard; there’s something important to fix, customers asking when it’ll be fixed, and executives wanting status updates. Break the problem apart and it’ll be way easier.

Now that incidents are out in the open, it’s possible to collaborate and break the problem down. A hero can take off their cape by taking the incident lead role and co-ordinating the response, or they can benefit from an effective leader running the incident process so they can focus on getting the fix out.

They can also switch between different roles in different incidents. Maybe there’s another team having their first incident in production and your hero can use their incident response superpowers to show them what an excellent incident leader looks like.

Spread the knowledge

With the vicious cycle of the hero-engineer broken, you can create a virtuous cycle instead. Incident response is now open for everyone to jump in, and your hero can take off their cape.

Rather than becoming burnt out and frustrated, the hero instead becomes an expert incident responder who can level-up everyone around them in how to react when things go wrong.

No more capes

Stepping back from being a hero is hard, and requires conscious effort.

It also requires care: if there’s a critical incident you might need to dust off the cape and take charge, but for most situations it’s healthier to make space for your teammates. This will feel uncomfortable at first, but it has a huge pay-off: it feels awesome the first time you show up to an incident and realise it’s all under control!

See related articles

The post-mortem problem

Post-mortems are one of the most consistently underperforming rituals in software engineering. Most teams do them. Most teams know theirs aren't working. And most teams reach for the same diagnosis: the templates are too long, nobody has time, nobody reads them anyway.

incident.io

incident.io

Keeping it boring: the incident.io technology stack

This is the story of how incident.io keeps its technology stack intentionally boring, scaling to thousands of customers with a lean platform team by relying on managed GCP services and a small set of well-chosen tools.

Matthew Barrington

Matthew Barrington

Secure access at the speed of incident response

Blog about combining incident.io's incident context with Apono's dynamic provisioning, the new integration ensures secure, just-in-time access for on-call engineers, thereby speeding up incident response and enhancing security.

Brian Hanson

Brian HansonSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization