Better learning from incidents: A guide to incident post-mortem documents

If you’re just starting out in the world of incident response, then you’ve probably come across the phrase “post-mortem” at least once or twice. And if you’re a seasoned incident responder, the phrase probably invokes mixed feelings.

Just to clarify, here, we’re talking about post-mortem documents, not meetings. It’s a distinction we have to make since lots of teams use the phrase to refer to the meeting they have after an incident. For those folks, we actually wrote all about best practices for post-mortem meetings here.

The world of post-mortem documents can be pretty divisive, though. Some argue that they’re an absolute must for incidents of all severities. Others will say they should be reserved for only the most severe of incidents–things like the once-per-year full-blown outage. And even in these cases, getting people to pull one together can be a very tall task.

Regardless of which side of the aisle you’re on, it’s hard to argue with the idea that post-mortems are a solid way to turn a not-so-good event (an incident) into something positive. These documents can help you distribute knowledge across your organization and build more resilient products and processes.

While we’re on the topic, it’s worth calling out that the phrase post-mortem feels a bit outdated, at least to us. Unless something's gone pretty terribly, it's unlikely anybody died, after all. We refer to them as incident debrief documents internally and commonly see other names like “Incident Retrospective” and “After Action Report” across incident.io customers. But because most of the world still refers to them as post-mortems, we’ll do the same here.

Either way, we’ve put together this article to answer all of your questions about post-mortem documents, including:

- A bit more on what they are

- A quick note on the concept of blamelessness

- Who should own them

- When you should actually create one

- How they can benefit your organization

What is a post-mortem document?

A post-mortem document is a space to gather information about an incident after it has been closed out.

The end goal is to better understand the contributing factors of an incident, key risks that might have been identified and plan out how you can prevent or reduce the impact of similar ones in the future.

Post-mortem documents typically follow a specific template

- Incident summary

- Incident timeline

- Contributors

- Mitigators

- Learnings

- Risks

A bit on blameless post-mortems

One phrase you’ll hear tossed around is “blameless post-mortems.” In summary, it’s an approach to post-mortems that calls for not scapegoating the person who “caused” an incident, and instead assumes everyone was well-intentioned and performing the best role they could given the information available. The more blame you toss around, the more toxic your culture will be and the less likely you’ll be to actually learn from your incidents.

While the idea of avoiding blame and focusing on contributing sounds good in theory, it can be problematic if taken to an extreme.

If you deliberately avoid talking about individuals involved in the incident, it becomes that much harder to diagnose how you can prevent it again. For us, mentioning someone in a post-mortem document is appropriate if it’s done in service of deeper understanding. Let’s use a really simple situation to highlight what we mean here.

Say someone has pressed a button that was the final trigger that led to an incident. In the post-mortem document, it’s OK to say they did so. But the follow-up to that should be:

- Why did they press that button in the first place? Was it improper training?

- Why does a button that allows things to break exist in the first place?

In this situation, not only does it make sense to mention someone by name, but it just makes sense to better understand the situation as a whole. Let’s call these accountable learning post-mortems.

Who’s responsible for creating a post-mortem document?

A sensible answer here is the incident lead. In reality, creating a post-mortem document should be a collaborative effort. In practice, the owner can be anyone who played a meaningful role in the incident.

The person who owns this document doesn’t necessarily have to be the person who caused it, or was even involved. They’re simply just the person who's tasked with getting it over the finish line, but everyone who was a part of the incident response process should chip in.

When you’re trying to designate a post-mortem document owner, consider someone who:

- Took a leadership role, e.g., an incident lead

- Took a specific action to resolve the incident

- Is on-call for the service that the incident affected

- Identified and manually declared the incident

Remember, the causes of incidents are never black and white. Creating these documents by committee allows you to gather as much information as possible from different stakeholders to figure out the best next steps.

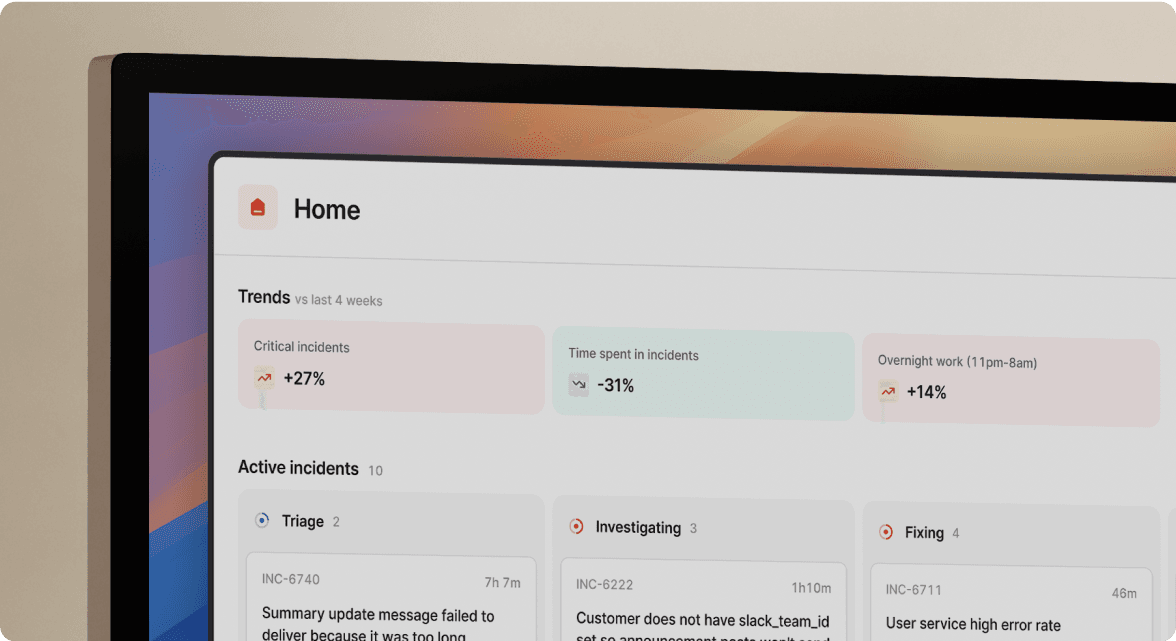

In an ideal scenario, the basis of your post-mortem documents is created automatically for you once an incident is resolved like they are with incident.io. This helps free up resources and automate what is admittedly a time-consuming process.

Why should you bother with post-mortems?

If creating a culture of continuous improvement and learning is a priority for your organization, then post-mortem documents are a great way to facilitate that.

The reality is that, in the middle of an incident, responders aren’t concerned about the full spectrum of underlying issues; they’re trying to resolve the incident. Post-mortem documents allow responders and the organization as a whole to reset and identify contributing factors.

Done well, these documents can unearth several areas of improvement you otherwise may not have found.

Issues like inadequate training, system vulnerabilities, misconfigurations, and process improvements can be discovered through a post-mortem. Under the focused attention of the post-mortem process, we have an opportunity to dig into how our organization really works—not just how we think it does!

When should you create a post-mortem?

To get the most out of them, post-mortem documents should be created shortly after an incident is closed out. If not, you and others risk muddying key details about the incident that can help diagnose contributing factors.

Preparation can take time, though, and particularly bad incidents can take a toll on the individuals involved, so it’s worth giving yourself some breathing room to collect your thoughts. It’s not uncommon for the people involved to develop a better understanding of an incident just as a result of taking the time to let things soak.

But we aren’t here to tell you that every single incident requires a post-mortem—we don’t do that ourselves here at incident.io! But if you have repeat incidents or ones that are particularly difficult to respond to, like intermittent downtime from repeat crashes, then the investment of time and effort to create a post-mortem is typically a good one.

Remember, the better you can understand underlying causes, the better prepared you’ll be for future ones or the more likely you’ll be to prevent these types of incidents in the first place.

Connecting learning to broader business goals

We’ve used the word “learning” quite a few times throughout this article. And while we write post-mortems to help drive a culture of learning from incidents, it’s important that we remember the learning is in service of the broader goals of the organization.

We wrote more about this in Learning from incidents is not the goal.

Using post-mortems to learn from your incidents can make a meaningful difference in how you manage future ones. However, focusing on learning as the goal instead of delivering value to customers is where organizations tend to go astray.

The journey of learning from incidents should just be a stop on the road to making the best product and providing the best service you can, not your sole reason for being.

So next time you’ve wrapped up a post-mortem, really think about how you can implement the learnings to provide more impact for customers. Remember, learning from incidents is not the goal—delivering value and positive business outcomes is.

More from Incident Post-Mortem guide

Our simple-to-use incident post-mortem template

Incident post-mortems are a crucial document that cannot be glossed over. In this article, you’ll find our go-to post-mortem template that you can use in your own organization.

Chris Evans

Chris Evans

A guide to post-mortem meetings and how we run them at incident.io

Post-mortem meetings can play a crucial role in fostering an environment of continuous learning. Here's how we do them!

incident.io

incident.io

Whose fault was it anyway? On blameless post-mortems

While blameless post-mortems are a great idea on the surface, if taken to the extreme, they can muddy how much you actually learn from incidents.

incident.io

incident.ioSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization