What I learned from leading my first incident

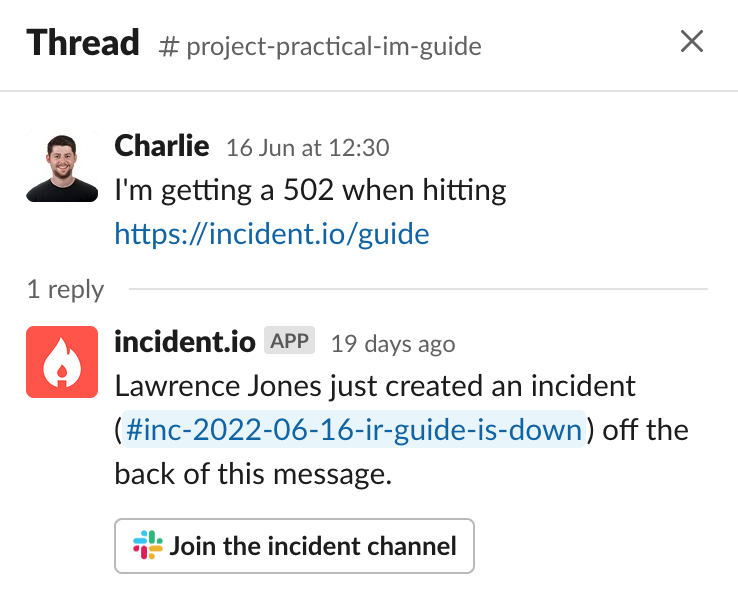

A few weeks ago we had a major incident. We were releasing our Practical Guide to Incident Management, and after posting about it online an incident.io employee noticed that the page wasn’t loading.

Just to set the scene, I’ve been at incident.io for 3 months and don’t have any experience of incidents in my previous role. When the team got paged I expected this to be one of those “follow along and learn how the wizards work their magic” exercises. But instead I was asked to take the lead.

The funny thing is, my day job revolves around incidents, and I’ve built parts of the incident.io product myself, yet I couldn’t work out what I was meant to be doing with the tools in front of me. Luckily I had an experienced firefighter giving me pointers, we steered the team and within 30 minutes the guide was up again.

The experience was undoubtedly the best thing I could have done to become a better responder, and I’d like to share a few things I learned.

1. Everything must go in the channel

A lot of discussions were taking place IRL, with a few people huddled around a desk at a time. This certainly allows for faster collaboration, but if you’re deep into your own investigation a few meters away you might have not heard about a crucial finding. As the Incident Lead it’s your responsibility to narrate everything you see or hear, provided it’s not already in the incident channel.

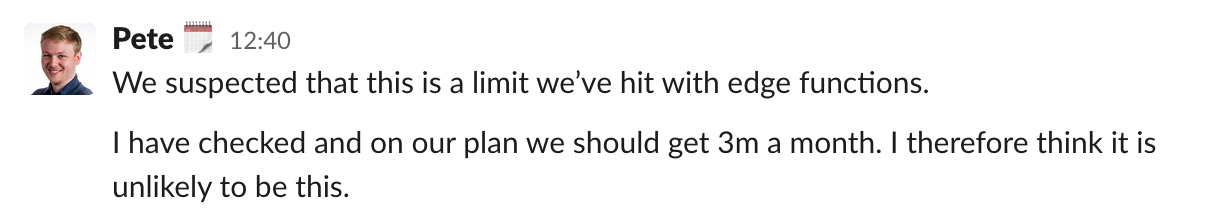

2. It’s okay if you don’t understand what’s going on

Everything about this incident’s root cause was way over my head. But even though I couldn’t follow conversations, I was able to interject with “That sounds like something new - should I make a note?” or “Does this change our next steps?”.

If you’re not sure what people are working on (ie. it’s not been conveyed in the channel) it’s also okay to ask them directly. We need a high level view of everything that’s happening in order to stop work being duplicated.

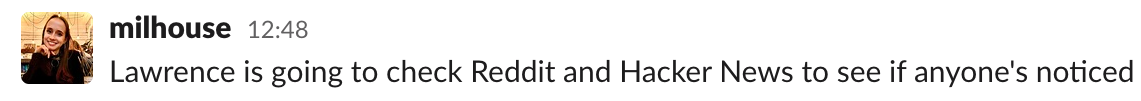

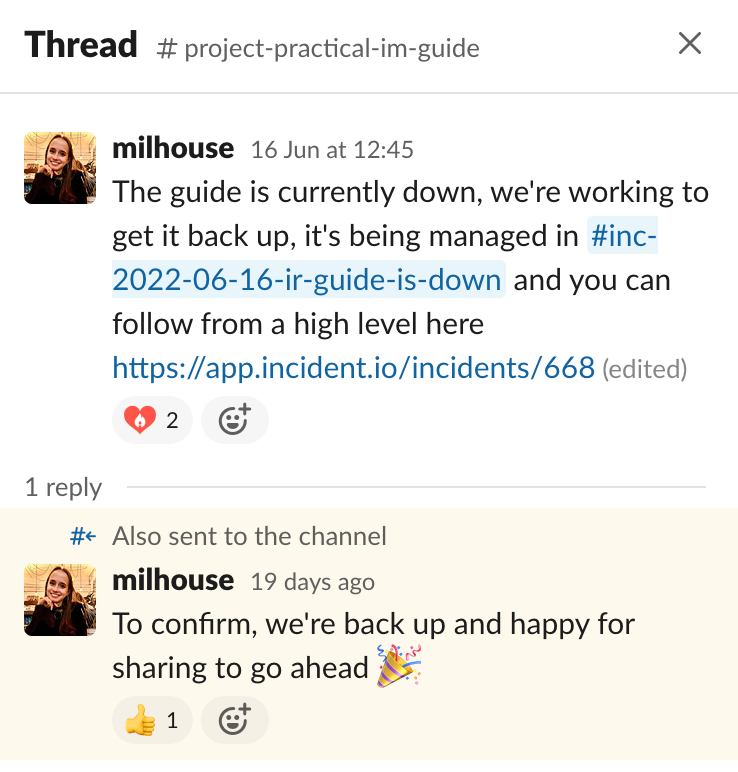

3. Provide updates as much as possible

It can be hard to follow when responders are moving quickly, but even harder to follow when you’re not in the room. Most of the marketing and customer success teams were remote that day and couldn’t necessarily digest the conversation in the incident channel.

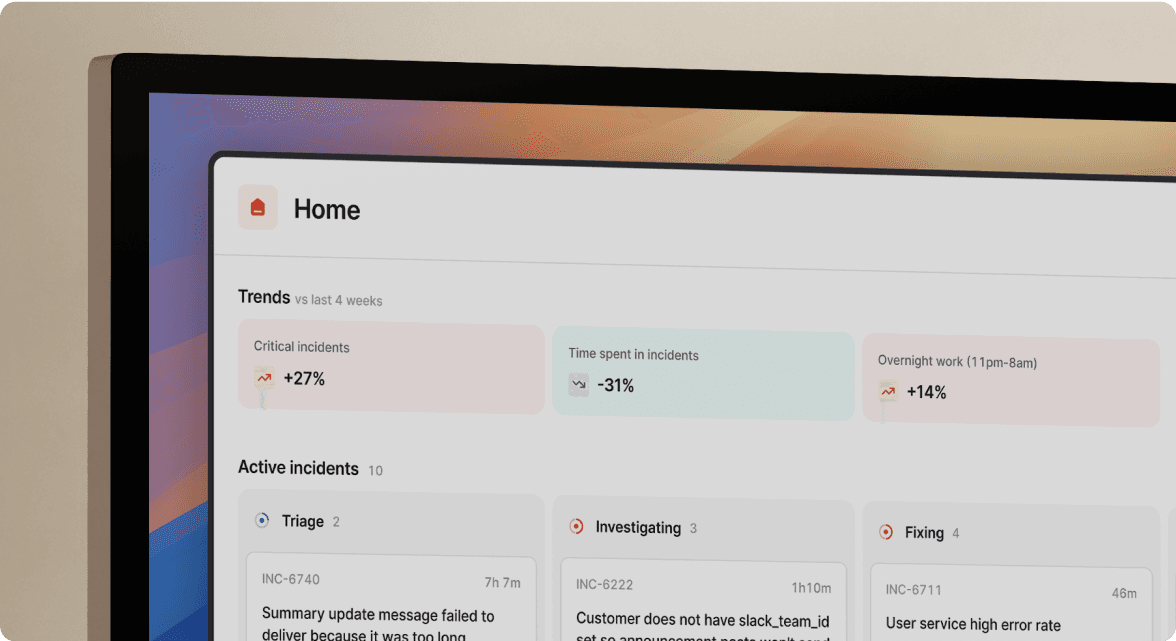

You should be constantly looking for opportunities to use /inc update so that you can translate findings into non-tech summaries. You can be even more proactive by linking affected teams or stakeholders to the incident homepage, where they can see the status updates and timeline of events.

4. Calmness is infectious

I probably wouldn’t have admitted it, but I was flapping internally when I got made the Incident Lead. However, the other responders were experienced firefighters and it showed: people were methodical and appeared very un-panicked by the situation. It completely levelled me out.

On reflection, the Incident Lead should probably be the calmest person in the room. They are not responsible for fixing or diagnosing the issue (which could be a big unknown), and panicking about other responders fixing it might put the responders off. An Incident Lead brings more value by not getting into the weeds of the problem. So next time I’m hoping to channel a zen-like attitude.

5. Break when necessary

The incident hit just as we were going for lunch, after a morning of back-to-back meetings. We were hungry. So when we brought the site back up with a temporary fix, we had to decide whether this was good enough so we could kick the “proper fix” down the road. We (or our stomach’s) decided yes, and we got ourselves some well deserved sandwiches.

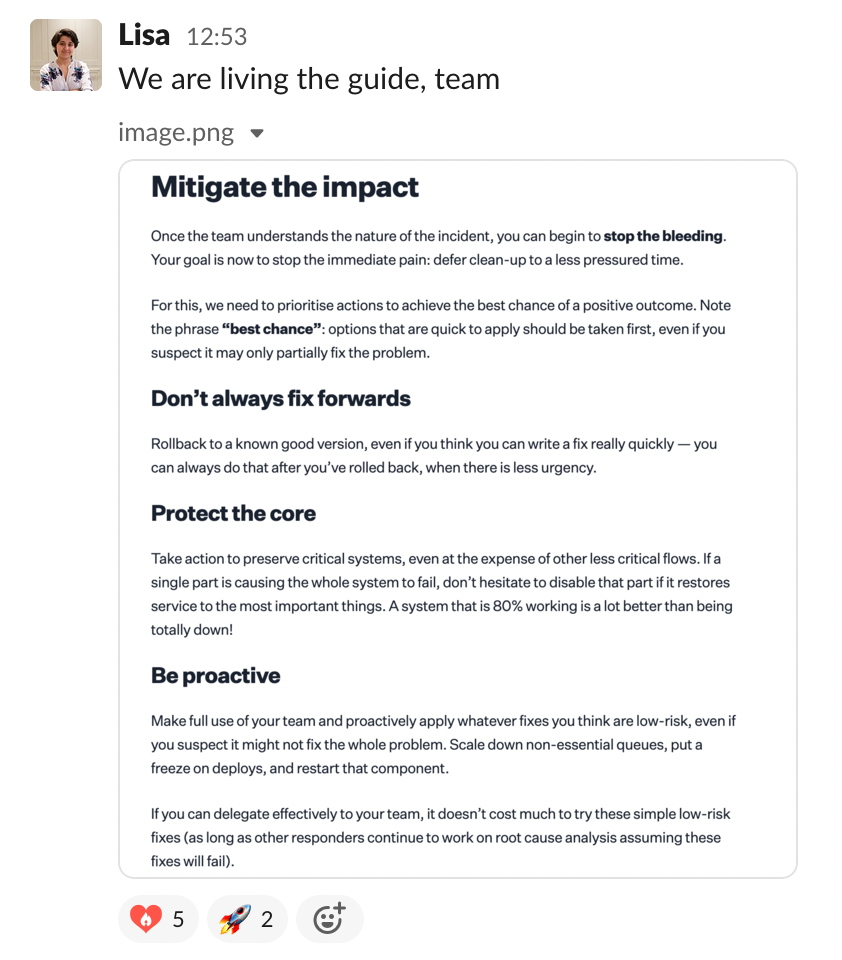

Ironically, there is a whole section about deferring clean-up in the Incident Management Guide we’d stabilised.

6. This was an incredibly useful exercise

If you have enough hands to help out, it’s worth asking an inexperienced responder to take the lead whilst an experienced responder prompts them. Don’t be afraid to do this for your major or critical incidents either; not only do they have the most people willing to help, but it’s worth getting used to the pressure before any important incidents in the future.

See related articles

The post-mortem problem

Post-mortems are one of the most consistently underperforming rituals in software engineering. Most teams do them. Most teams know theirs aren't working. And most teams reach for the same diagnosis: the templates are too long, nobody has time, nobody reads them anyway.

incident.io

incident.io

Keeping it boring: the incident.io technology stack

This is the story of how incident.io keeps its technology stack intentionally boring, scaling to thousands of customers with a lean platform team by relying on managed GCP services and a small set of well-chosen tools.

Matthew Barrington

Matthew Barrington

Secure access at the speed of incident response

Blog about combining incident.io's incident context with Apono's dynamic provisioning, the new integration ensures secure, just-in-time access for on-call engineers, thereby speeding up incident response and enhancing security.

Brian Hanson

Brian HansonSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization