Trust shouldn’t start at zero

How often have you heard the phrase “trust is earned” in life? While well-meaning, I think this can actually lead to some strange behaviour at work, especially when you’re on a fast growing team.

Startups experience a lot of chaos and unknowns your teams need to navigate, so it’s vital to know you can trust the people around you. As you grow, how you set expectations around trust as people join your team can impact your ability to hire, onboard, ship and ultimately, survive.

In this post, I cover some thoughts on how I encourage folks here to think about trust when new people join our team.

The “trust scale”

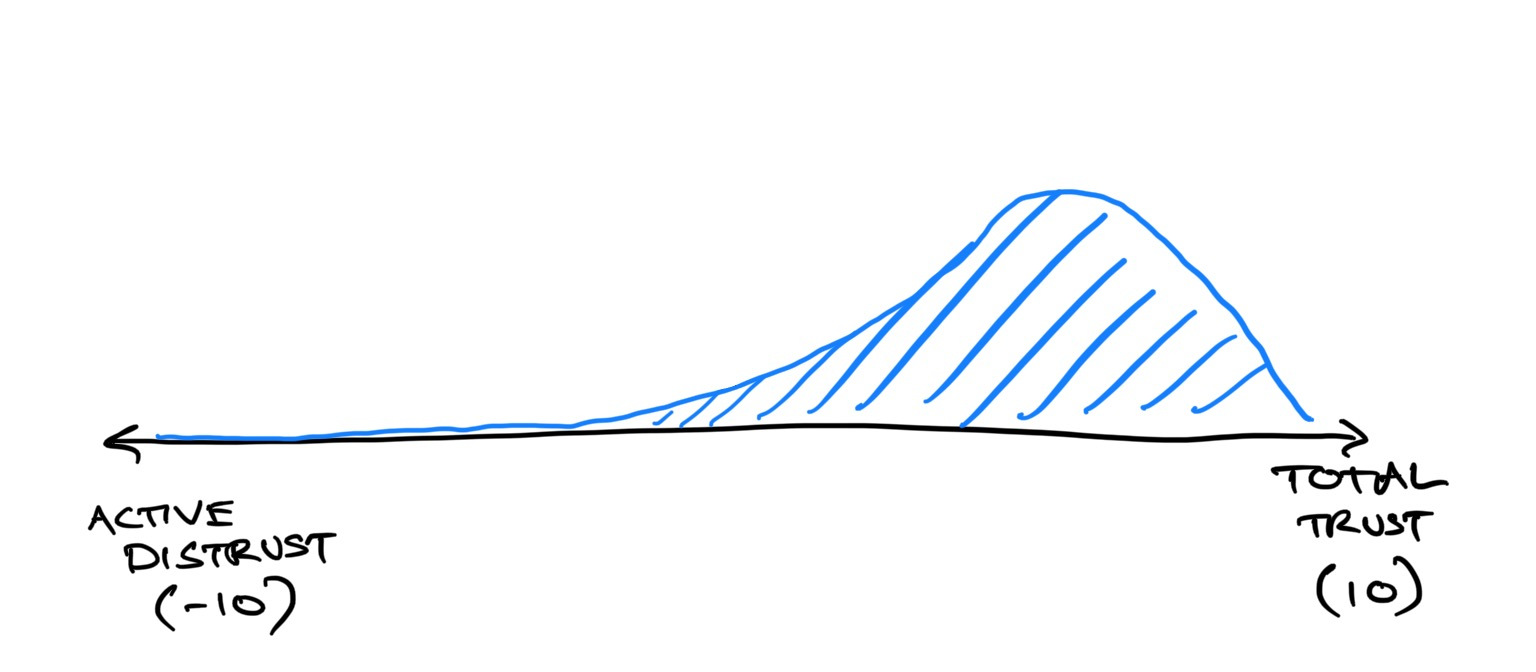

Everyone loves a good two-point scale, so let’s imagine a line from -10 (active distrust) to +10 (total trust).

If you drew a curve representing most of your day-to-day relationships, it’d probably (hopefully) sit somewhere to the right, and maybe look something like this:

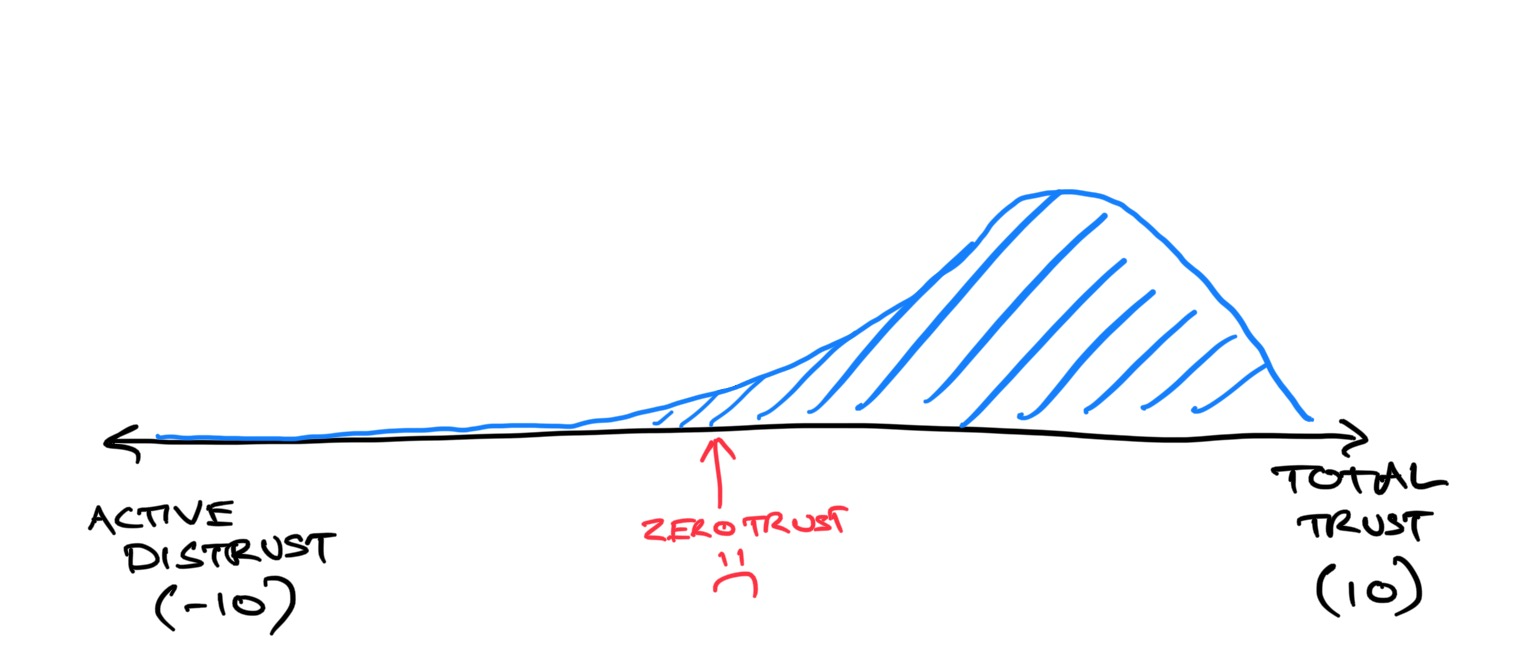

When someone joins a team, it’s not uncommon for the existing people in that team to take a “trust is something you earn” mentality a bit too literally.

All too often, a new person is expected to turn up and “earn their stripes, just like everyone else did” and until they do, whether it’s subtle or overt, there can be an air of “let’s see how it goes” that hangs over them. In many ways, they start with a trust level of zero.

As the new person on the team, being on the receiving end of this is pretty intimidating.

You can easily spend all your time wondering “if I get this wrong, is that it!?” and it feels as if any mistake might put you in the “they don’t trust me” camp with new colleagues.

Being actively distrusted potentially means a risk of fewer opportunities, less autonomy, being overlooked or even actively avoided, all of which make it even harder to earn back the trust and respect of your team. Unfortunately, I’ve seen this happen first hand. You probably have, too.

I didn’t always see it this way

In my early days as a manager at a past company, we hired several new leaders to help us scale the team. I’d moved into the role internally, a huge advantage in hindsight and one which I didn’t fully appreciate at the time.

To start, I struggled to figure out how to trust my direct reports, and what to trust them with.

Would they really know what our teams needed, having never worked on them or the company before? I certainly didn’t actively distrust them, but I definitely didn’t initially give them as much of my time and trust as I should have. I was cautious.

I’d look at decisions they made and judge them on face value. They were a manager, I was a manager, they’d done this more than I had, why on earth would they do it that way!?

What I had failed to grasp was the privilege of the context I held. They were making the best decisions they could, with the information they had. When I perceived a misstep, rather than immediately offering up context and support and giving them a chance to re-assess (or help me learn from them!), I notched them down a bit on my trust scale.

When one of the managers later left the business (amicably) they gave me some parting feedback: they’d enjoyed working together, but they hadn’t quite felt like I fully engaged with them when they first joined. They wished we’d collaborated more early on.

This really changed my perspective—they wanted exactly what I wanted, a high-trust relationship. The perception that I didn’t fully trust them had made it more difficult for them to put themselves out there, risking damage to the trust they’d built or treading on my toes.

On reflection, I’d been holding back a bit too much until they “proved themselves” but I had tonnes of social capital with the team and loads of context. I’d been waiting for them to “earn my trust,” but the trust was mine to give.

Trust is not earned, it is given

If you’re the person joining a new team, this is also an important concept to grasp, I think.

In the same way we don’t really sell products (customers buy them!), you shouldn’t view trust as something you can magically achieve because you did the right things. Trust is not an adversarial game to be won, it’s something someone has to give to you freely. Nothing else counts.

It’s a very subtle mindset shift, focussed more on the other person, but I think it’s a useful one.

While it’s certainly true that a lot of professional behaviours that can build trust are transferrable and can apply to many people, giving people your trust is a very individual thing. What earned you trust in previous jobs and with previous colleagues there may not be what encourages people to give you their trust here.

One example of where this applies is hiring leadership and managers.

Often these are strategic roles, but producing a strategy document is rarely how you build trust on day one. Some of the best leaders I’ve worked with started by simply asking what the immediate challenges were, then buckled down and did whatever needed to be done.

It wasn’t sexy or strategic, but it addressed things that mattered to me and my team, which built up trust quickly. This made it easier for me to give them more of it when it mattered most (a re-org, or a strategic shift).

As the person on the existing team, you also benefit from taking note of this framing. The person joining probably doesn’t know how to build trust with you yet. Show them. Take the time to chat about what matters to you. Give them opportunities to build that trust and if they miss the mark, to try again.

Trust shouldn’t start at zero

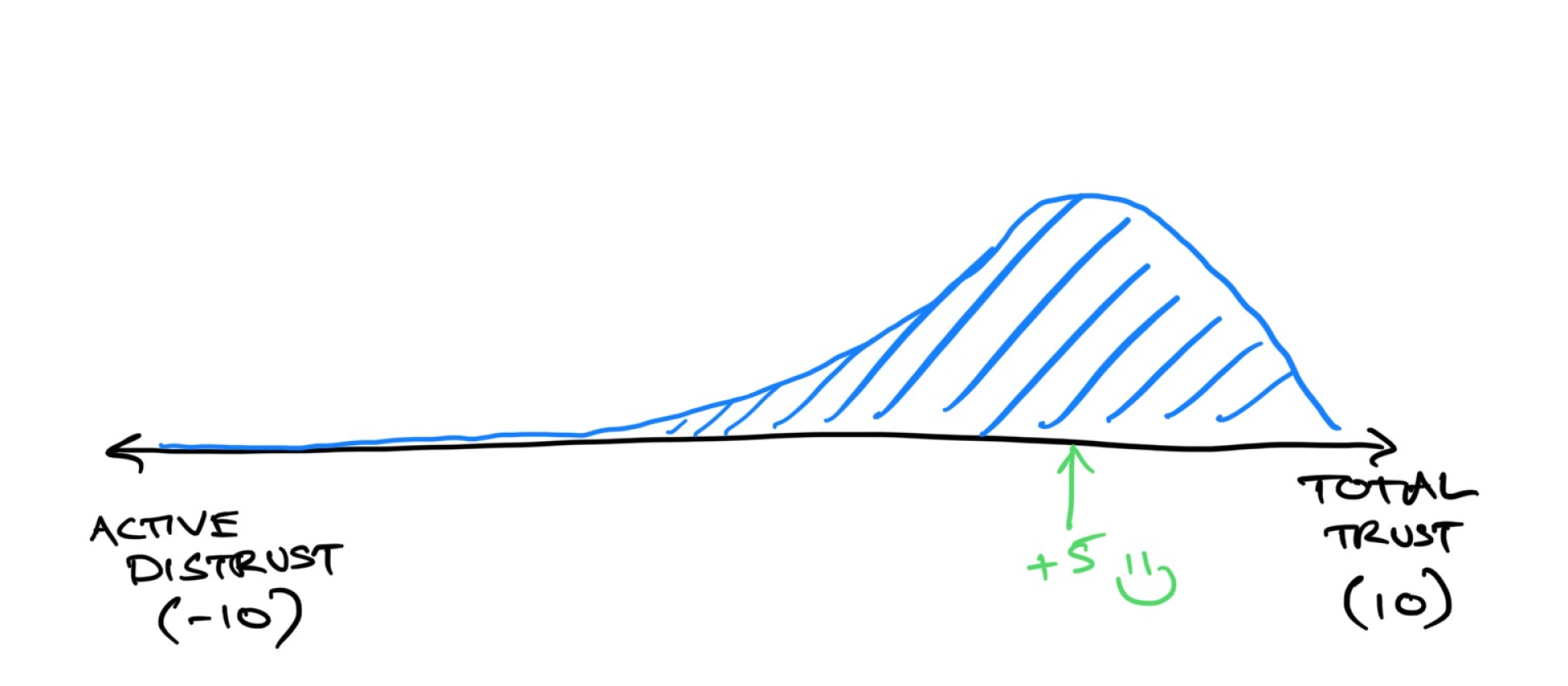

Coming back to our trusty scale, you might be asking the obvious question of “why not start trust trust levels at 10 then? After all, didn’t you just say we should be much more trusting up front?”

Obviously, when someone joins your team, you hope they’ll do an amazing job (otherwise why did you hire them!?), but it probably isn’t sensible to blindly trust them with everything right away, either.

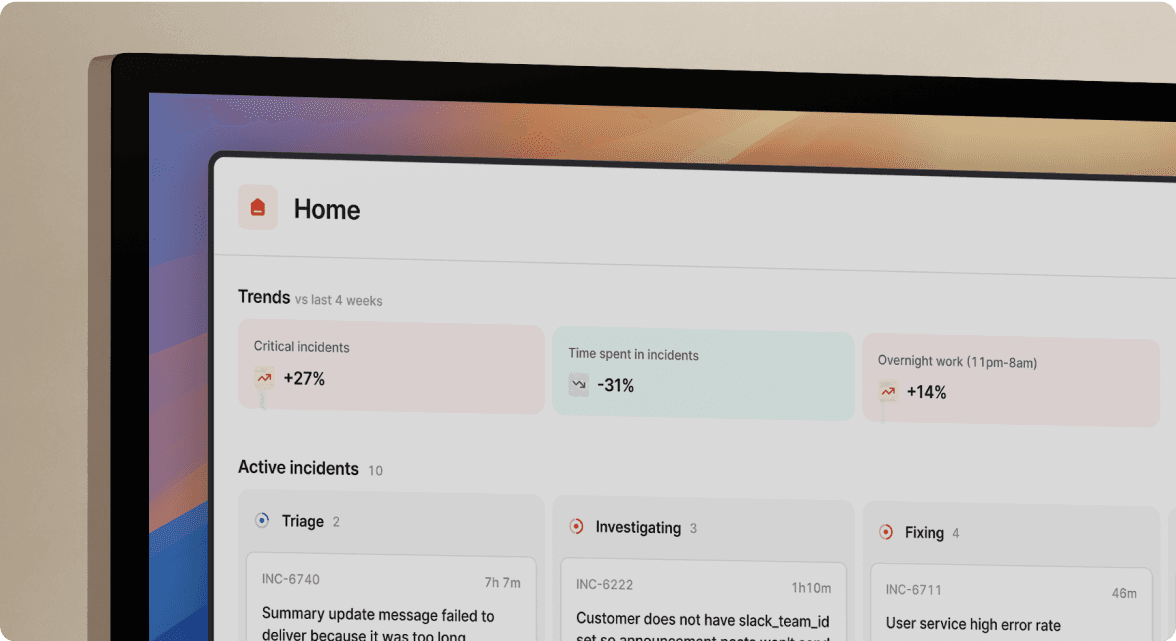

Some ways we extend trust early on at incident.io include:

- Engineers leading projects within their first month. Typically the domain of more senior members of the team, at incident.io it's normal for folks to be running projects as part of their onboarding. You're supported, but explicitly trusted, too.

- Everyone gets a company card with a limit they can use to buy things to make them more effective. In some companies, buying a book requires triple signoff. Here you can buy a keyboard, chair, laptop stand or coffee with a colleague and until you hit your limit, we don't even look.

- We put people in front of customers within their first month or two. We hired you, we trust you and we want you to build confidence chatting with customers and being a voice of the company. It's not uncommon for engineers to join calls shortly after starting, or for customer success managers to demo part of the product in their first week.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, some examples where we would hold back a bit might be:

- Putting a new Infrastructure Engineer on-call in their first week. Even if they’re fantastic, they probably don’t yet know everything required to run an incident at 1am, when the app has gone down and nobody can log in, for example!

- Letting people make major process changes without trying things our way first. The changes may well be improvements, but we like people to wait until they've had some time to really understand how we work and the implications, direct and indirect.

Instead, I suggest setting your trust level to about “5” on our imaginary scale. Conveniently that’s also exactly where my hypothetical distribution peaks. How about that.

This keeps some trust in reserve, giving them room to build more, but gives them enough so they can fail and still succeed. The idea that it needs to be OK to mess up is especially true at a fast-growing startup where you actively want people in your business to take some risks (which are often how you find the biggest upsides!).

Playing it safe is not the name of the game here.

The best people will also learn from those failures, pick themselves back up and take another shot and will likely appreciate being given the chance to do so.

Trust me

Being able to say the words “trust me” and know that the person will, or hearing “trust me” from someone and knowing that you can, are huge advantages when you need to make decisions quickly and when change is constant.

So before the next person joins your team, ask yourself if you’re setting your trust level appropriately and next time things aren’t going so well, start by asking where your trust level is currently set.

It’ll help. Trust me.

See related articles

Keeping it boring: the incident.io technology stack

This is the story of how [incident.io](http://incident.io) keeps its technology stack intentionally boring, scaling to thousands of customers with a lean platform team by relying on managed GCP services and a small set of well-chosen tools.

Matthew Barrington

Matthew Barrington

Secure access at the speed of incident response

Blog about combining incident.io's incident context with Apono's dynamic provisioning, the new integration ensures secure, just-in-time access for on-call engineers, thereby speeding up incident response and enhancing security.

Brian Hanson

Brian Hanson

Everything you need to know about ITIL 5, AI and incident management

We break down ITIL 5's governance framework and what it means for teams using AI in incident response. For incident management, it addresses questions like: Who's accountable when an AI-suggested remediation backfires? How do you audit AI-generated updates?

Chris Evans

Chris EvansSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization