Why more incidents is no bad thing

For a long time we've anchored ourselves to the notion that we should have fewer incidents, or none at all. It's hard to argue against — why wouldn't we want to fewer things to go wrong?

Incidents are a deviation from what we've defined to be the happy or expected path, and typically correlate with a negative or undesirable outcome. Surely having them happen less often makes sense?

Compare two identical organizations, differing only by the number of incidents they have. Logically, you might think the one with fewer incidents is performing better. It might be, but it's not that straightforward — the fewer incidents we have, the less information we have to hand, and the harder it is to know either way. Everything could be fine, or we could failing to report or missing problems altogether — we're flying blind.

The Deepwater Horizon oil rig incident is a perfect example. It held an impeccable record of zero safety incidents for seven years. On the eighth year, it suffered an explosion causing one of the worst oil spills in history. Post incident analysis concluded systemic failures on the rig that, if surfaced, could have prevented the critical incident. This information wasn't readily available to right people at the time which meant there was no opportunity to intervene.

If your organization has no incidents, maybe things are working perfectly, or maybe there are little fires everywhere, waiting to develop into the next organizational inferno? In that case, I'd wager you'd want to grab that fire extinguisher rather than evacuate and call out a fire crew.

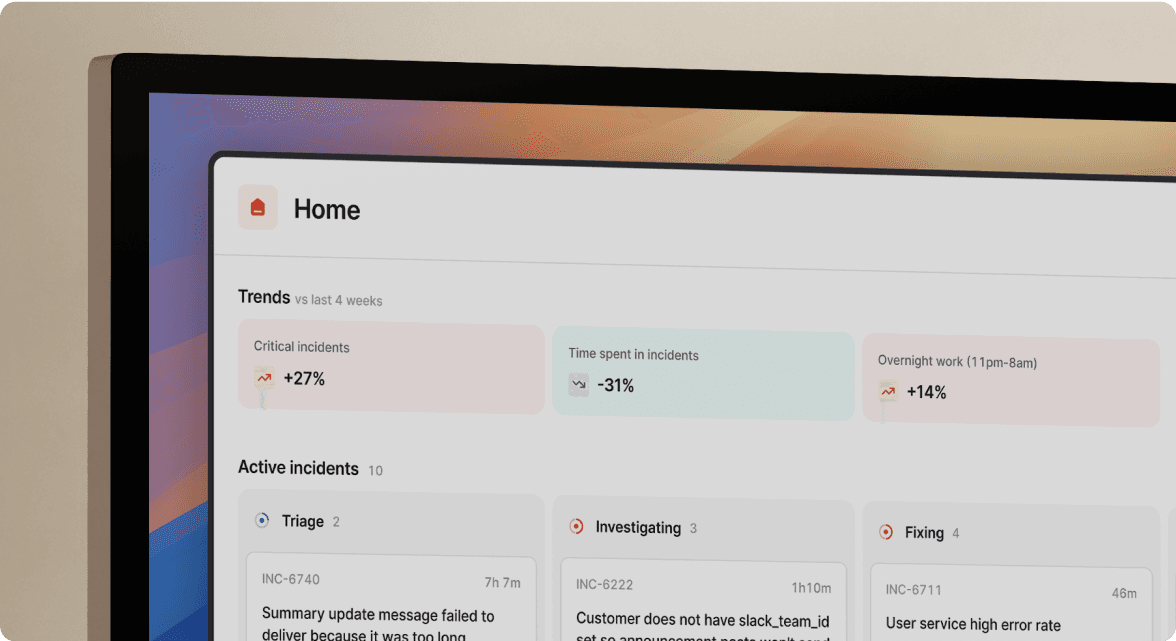

At incident.io, we believe organizations should target a healthy incident culture, where incidents are seen as an acceptable cost of doing business. Rather than working to eliminate them, we should embrace them head on, make them more visible, and optimise for learning to maximise the value we derive as a result. In practice this means creating an environment where people are encouraged to report, given space to learn, and where the threshold to classify an incident is set deliberately low.

In such an environment, incidents provide a window into how things really work — an insight that goes beyond work as it's imagined or written on paper. Take the system that breaks and causes an outage. Often these failures will be the result of mismatch between the way engineers think the system will behave and how it actually behaves. The incident is unavoidable, but the insight leads to learning, the learning develops expertise, and expertise leads to better decisions in future.

By embedding a healthy culture of incidents where increased visibility not just acceptable but also desirable, organizations can course correct early and often. As David Marquet said: "a little rudder far from the rocks is a lot better than a lot of rudder close to them". Incidents are your binoculars, focused on the rocks, and they'll help you apply that rudder long before you're in trouble.

I'm one of the co-founders, and the Chief Product Officer here at incident.io.

See related articles

The post-mortem problem

Post-mortems are one of the most consistently underperforming rituals in software engineering. Most teams do them. Most teams know theirs aren't working. And most teams reach for the same diagnosis: the templates are too long, nobody has time, nobody reads them anyway.

incident.io

incident.io

Keeping it boring: the incident.io technology stack

This is the story of how incident.io keeps its technology stack intentionally boring, scaling to thousands of customers with a lean platform team by relying on managed GCP services and a small set of well-chosen tools.

Matthew Barrington

Matthew Barrington

Secure access at the speed of incident response

Blog about combining incident.io's incident context with Apono's dynamic provisioning, the new integration ensures secure, just-in-time access for on-call engineers, thereby speeding up incident response and enhancing security.

Brian Hanson

Brian HansonSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization