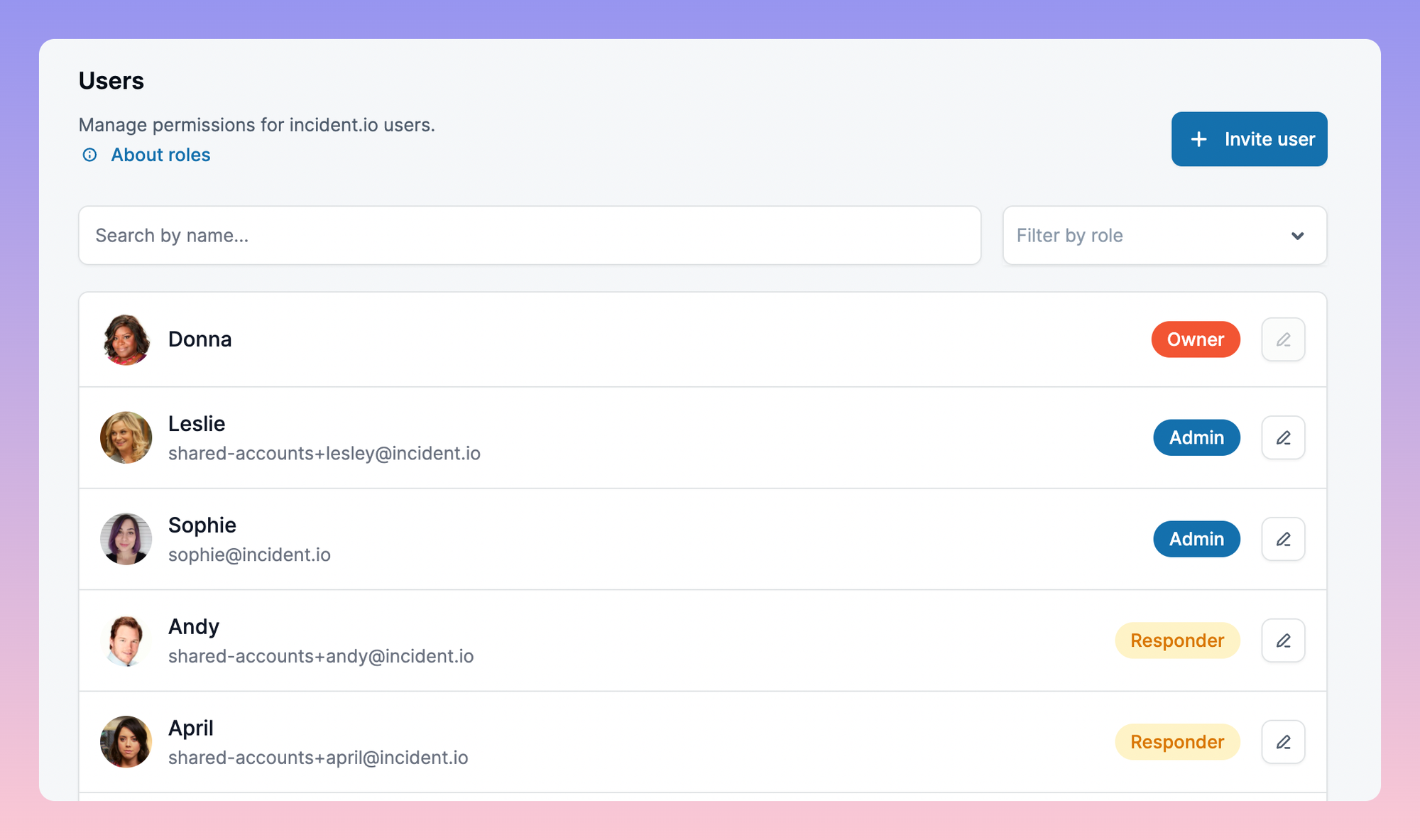

Rolling out Roles

We rolled out user roles a few weeks ago, and this post goes behind the scenes with how we:

- Decided we needed to build in user roles

- Worked out how we wanted to build them into our backend

- Made sure our frontend codebase can handle these well without slowing us down

- Worked out how to assign roles to our existing users, and rolled this out gradually

You didn’t have roles before?!

We’ve been pretty lucky at incident.io to be able to avoid dealing with more complex authentication issues for quite a while, because we piggy-back on Slack to know who you are and which organization you work in. Whole companies have been built around doing authentication and user profiles really well, so it was pretty neat to be able to avoid doing most of that work for so long!

We’ve known we won’t be able to avoid tackling this problem for ever though. There are a few features on our roadmap that will require permission levels, but the launch of Private Incidents, made us realise that we couldn’t put this off any longer. Some people would need to be able to have oversight of even private incidents, but we couldn’t let everyone do that, or they wouldn’t really be private any more.

Some definitions

Before we begin, there’s some jargon in the world of permissions that will help here:

- a “role” is a set of permissions a user has, that might be shared by multiple users

- a “scope” is a specific permission, e.g. “update billing info” or “add a new Custom Field”

Keeping it simple

As anyone who’s ever built anything in Google Cloud or AWS will tell you, there are some incredibly powerful and flexible permission models around, which are essential for big, complex, and flexible cloud platforms, but would be a burden for us to maintain, and for our customers to use.

On the other hand, we don’t want the permission levels we decide when we’re a small company to become constraints we’re always hitting against a few years down the line.

Our middle ground is to have a fixed set of roles that we offer to all our customers, but which become a set of granular scopes behind the scenes. That means we only have to define things like “an owner can see private incidents” and “administrators can change billing info” in one place, but the billing flow just asks “can this person change billing info?”

We rolled this check into our existing getIdentity function which gets the authenticated organization from the request context:

func getIdentity(ctx context.Context, requiredScopes ...rbac.Scope) (*domain.Organisation, *domain.User, error) {

...

// Check that all scopes are present on the user.

for _, requiredScope := range requiredScopes {

if err := rbac.Ensure(ctx, org, user, requiredScope); err != nil {

return nil, nil, err

}

}

return org, user, nil

}

That means adding permissions to checks to all our APIs was really simple:

func (svc *announcementRulesService) Create(ctx context.Context, payload *announcementrules.CreatePayload) (*announcementrules.CreateResult, error) {

- org, creator, err := getIdentity(ctx)

+ org, creator, err := getIdentity(ctx, rbac.ScopeAnnouncementRulesCreate)

We also needed to make the frontend app aware of these permissions, otherwise we’d waste people’s time letting them make a whole bunch of changes they aren’t allowed to save.

Our type-safe generated client made this much simpler! We include the list of possible scopes as an enum in our API design, which means the frontend can refer to scopes in a type-safe way. We return the user’s current list of scopes to the frontend as part of their identity, so checking if something should be available is relatively neat:

const hasScope = (scope: ScopeResponseBodyNameEnum): boolean => {

return identity?.scopes?.map((x) => x.name).includes(scope);

};

We can now have lovely safe components like a GatedButton that can disable itself for anyone without the relevant scope, and tell you why you're locked out ⛔

Feature-gating the rollout

This isn’t the kind of feature you want to just ship all in one go, because there’s so many ways it can go wrong:

- if the wrong people are made owners, they’ll be able to see private incidents that we’ve been so careful to keep private 😬

- if no one gets any elevated role, lots of settings will be locked forever 😬

- someone who is in the middle of changing some settings might get locked out of changing them 😬

We solved this by putting our users in control of when they want this feature. This is a new timestamp that we store for each organization which marks when we’ll start applying permissions for them. We set a deadline of March 1st for turning this on, but any organization owner could opt-in earlier than that.

Before that deadline, all our other features will work as before, but even owners won’t be able to see everyone’s private incidents.

How to pick initial owners and admins

That meant that getting our initial choice of owners and admins wrong was less risky: although a poorly-chosen owner could hit the “enable roles” button and see all private incidents, that would be an active bad choice from them. However, we didn’t want to make everyone an owner and let people lower privileges manually - that would be a huge amount of work for some of our larger customers!

We started by thinking about how we’d handle this for new signups. The only option there is to make the first person who installs incident.io the account owner, so we decided to treat our existing customers in the same way, and send the chosen owners a message asking them to make sure to re-assign it if we’d made a poor choice.

For administrators, we looked at product usage data, and identified anyone who’d done anything that would require the administrator role in future, and made them an administrator. Our message to the owner made it clear that they should review the administrators as well, and for most organizations this was pretty close to correct.

Putting it all together

This meant we could build and test the new permissions system behind the scenes, and safely roll it out to our existing customers over a month.

As our product grows in complexity we’ll be able to extend this system, but for now it’s nice and simple for us to understand, and hopefully easy to use too.

See related articles

The post-mortem problem

Post-mortems are one of the most consistently underperforming rituals in software engineering. Most teams do them. Most teams know theirs aren't working. And most teams reach for the same diagnosis: the templates are too long, nobody has time, nobody reads them anyway.

incident.io

incident.io

Keeping it boring: the incident.io technology stack

This is the story of how incident.io keeps its technology stack intentionally boring, scaling to thousands of customers with a lean platform team by relying on managed GCP services and a small set of well-chosen tools.

Matthew Barrington

Matthew Barrington

Secure access at the speed of incident response

Blog about combining incident.io's incident context with Apono's dynamic provisioning, the new integration ensures secure, just-in-time access for on-call engineers, thereby speeding up incident response and enhancing security.

Brian Hanson

Brian HansonSo good, you’ll break things on purpose

Ready for modern incident management? Book a call with one of our experts today.

We’d love to talk to you about

- All-in-one incident management

- Our unmatched speed of deployment

- Why we’re loved by users and easily adopted

- How we work for the whole organization